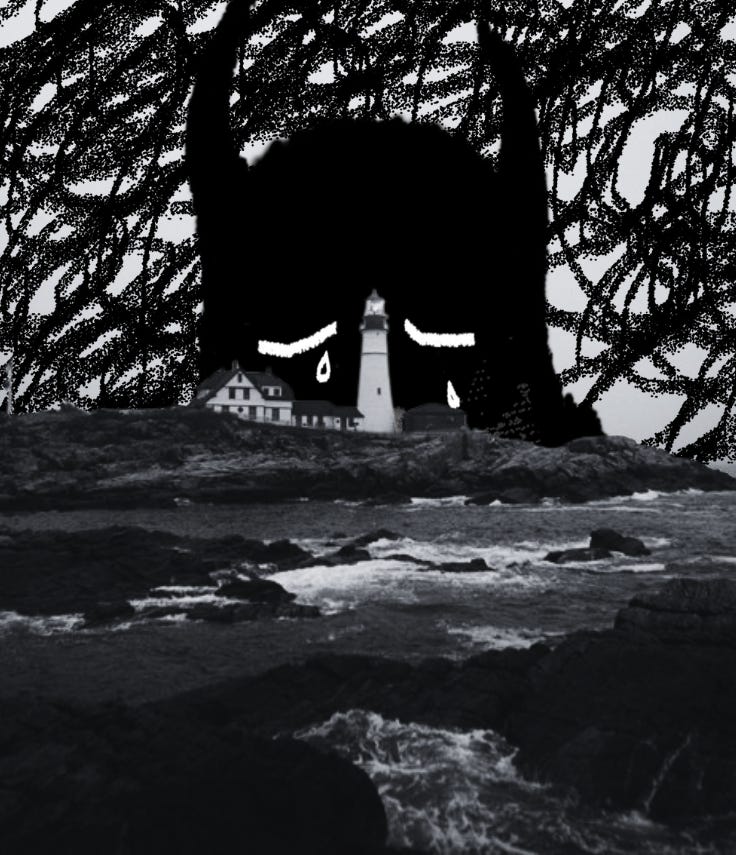

monster

for children who have not known love

“You’re not a monster,” I said.

But I lied.

What I really wanted to say was that a monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin root monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.”

— Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

One moment, you are a child.

You are small, and afraid, and at the mercy of adults who neither care for you nor have any objections to causing you harm. Of course, you don’t know that. Not yet. For now, you have simple, innocent desires, and you seek them out based on things you know intuitively: you’re hungry, and so you want to eat. You’re tired, and so you want to sleep. You crave affection and attention from your primary caregivers and guidance from adults outside your home, and so you seek these things as all children do, having no reason to believe that your very human needs will be met with anger or cruelty.

The first time an adult meets your attempts at affection with pain or punishment, you don’t blame them. You remember that you’re small, which means you live by a singular, all-encompassing rule: you obey the people bigger than you. How you feel about it doesn’t matter. So when adults react to your requests for care with hostility, or hurt you when you learn things the hard way, or subject you to things no adult should ever do with or to a child, your instinct isn’t to assume that they’re wrong. You wonder instead what you did to make them treat you that way. You blame yourself and, with the desperation of a hungry dog fighting for scraps, vow to do better next time.

Only next time isn’t any better. Neither is the time after that. This is bad. You rely on the adults for everything. You’re small and unlearned in the ways of the “real world,” and they don’t always say it out right, but you’re smart enough to see the unspoken threat: the adults could take it all away if they wanted to. If you make them angry or upset them for any reason, they could deprive you of necessities, keep you isolated and confined, hit you where it hurts. They could do whatever they want because they’re adults, and you’re small, and there’s nothing you can do to stop them.

At home, the punishments get worse. Elsewhere, the invasions of your body are scary and painful. As time goes on, you still don’t know what it is you’re being punished for or what the invader hopes to find, but it all becomes relative. It becomes normal. You’ve never known anything else, and after living like this for so long, you accept that you deserve it. Blaming yourself comes as easy as breathing. The soft heart of your human needs keeps crashing against the brick wall of the adults’ anger and aggression, and you reason that there is simply no other logical explanation. Why else would those tasked with your protection be the ones to break you?

Still, some distant part of you — one you often avoid and feel ashamed to acknowledge — questions if this is really how it’s supposed to be. You meet other children who seem unafraid of their families, who seem to have no knowledge of the things you’ve been forced to do and witness, and you wonder, what about me? So, despite everything you’ve learned, despite all the signs pointing to you as the one solely responsible for your problems, you dare to venture beyond the bounds of your familiar, fractured hell. You secretly hope to hear that what’s happening to you is not normal and that there are adults out there somewhere willing to give you the safety you’ve always wanted.

The first time an adult meets your pleas for help with pain and punishment, you don’t blame them. You don’t blame them any of the times after that, either. Some simply ignore you. Others take part in your torment, but that’s fine because you deserve this. This is normal. You’re small. The last time you beg someone to save you, you think that maybe your human needs don’t matter.

You think maybe you’re not human at all.

Previously called Multiple Personality Disorder before being renamed in the 1990s, Dissociative Identity Disorder is a mental health condition characterized by the presence of two or more distinct states of consciousness and identity, referred to colloquially as “alters.” Alters can have markedly different behaviors, memories, opinions, and ways of engaging with the world. For all intents and purposes, Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is the coexistence of multiple different people — often referred to collectively as a “system” — within a single brain.

Risk factors for developing DID are as follows: severe and repeated childhood trauma, such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; trauma occurring before the ages of 7-10, particularly trauma that involves interpersonal violence, neglect, or unstable environments; and disorganized attachments to the primary caregivers.

Contrary to popular media depictions of it, which would have you believe that it’s a psychological superpower or a means of keeping criminal behaviors at bay, DID is a defense mechanism. It’s an involuntary response a child’s brain may employ to protect them from the trauma they’re experiencing. Different alters emerge to satisfy different needs within a system, and the amnesia between them protects the system — particularly the “host,” or the alter who participates in daily life most often — from the knowledge of their trauma. It’s common for people with DID to forget parts of their lives and experience day-to-day memory loss referred to as “losing time.”

According to the research we currently have at our disposal, DID develops through repeated and complex childhood trauma. Abuse is not the only type of trauma that can cause DID, though it is a frighteningly common experience among systems. In addition to being heavily stigmatized, misrepresented, and misunderstood by both laymen and professionals alike, DID can be challenging to accept as a diagnosis by the nature of its function, which is to keep traumatic memories away from a child’s conscious awareness. Since DID forms with the explicit purpose of compartmentalizing information and withholding things to keep its host alive, the brain can also, by extension, conceal the existence of the system itself to keep you safe from the reasons your system exists in the first place. This is why denial is such a common symptom among those with the disorder; the brain is hard-wired to hide the DID, even (and especially) from the people experiencing it.

The next moment, you’re 17.

You’re on the brink of what you think will be freedom. Soon, you’ll get to make your own rules, have your own resources, create your own reality. The other adults are still bigger and older, but they won’t be in charge after you graduate. You’ll only have to answer to yourself, which means no more pretending. No more punishments. No more pain.

There’s just one seemingly unsolvable problem: you’re pretty sure you might be losing your fucking mind.

You keep telling yourself you’re fine, that nothing is wrong with you, it can’t be, because that would make them right — but your symptoms suggest otherwise. You never thought anything of it. Sure, you think about dying all the time. Sure, sometimes, you startle so hard, you feel like fainting, or you get so anxious in public, the whole world starts to spin, but you used to be able to manage all that. Once, you could keep up the ruse that you’re something close to normal. Now, you’re scared to go to sleep. Scared to be awake. Scared to leave the house because sometimes, all it takes is a sound, or a word, or a smell to send you spiraling. You feel impossibly fragile. You’re certain this is the worst it’s ever been, but you also don’t really know what it is, and you can’t remember what came before this, and suddenly, you’re keenly aware that you can’t remember much of anything at all.

You realize you have gaps in your memory. Years of your life, gone. It hits you how often your siblings tell stories from childhood that you don’t remember. How many times you’ve struggled to answer simple questions about your life before high school. It never occurred to you before that this level of memory loss might not be normal, but now, you’re tallying all the time you can’t account for, and it’s not just the lack of memories. You can’t remember things you did today. Yesterday. Last week. You’re losing time now, and the evidence of it is everywhere.

You find journal entries in unfamiliar handwriting. Messages scrawled out in sharpie on the underside of your desk. Your things are scattered to places you wouldn’t have put them, and there are shards of broken mirror and torn up pictures in the trash. You’ve never told anyone for fear of being committed, but sometimes, when the panic comes and you can’t claw your way out of it, you black out. You never really know how long you’re gone. All you know is that when you come to, you’re covered in cuts and bruises you can’t explain, and you — or some other version of you, maybe? — bloodied your knuckles on a brick wall.

But that’s not all. The last piece of this fucked up puzzle, the piece that scares you the most, is that you keep hearing voices in your head. There are many, and they’re not always talking to you. You can’t control them or turn them off, so you just try to ignore them, but that doesn’t always work. When it does, you get this bizarre feeling that you’ve upset someone, but how can you upset someone that lives in your head? How can you hurt a hallucination? And if it’s not a hallucination, then what is it?

None of it makes any sense. You tell yourself you’re crazy and file it away as yet another sign that you’re broken — or worse.

I’m not human, you think.

I’m a monster.

Mr. Robot: “If I could go back in time and change everything that happened to you, make it all go away…”

Elliot: “Then I wouldn’t be me. And I wouldn’t have you.”

— Mr. Robot, Season 4, Episode 8

If I’m being honest with you, I’ve seen the signs all my life.

Little clues that something was happening inside of me that I could neither understand nor explain. I didn’t have the language to describe my experiences. No point of reference to use as a sounding board for all these symptoms with seemingly no specific origin. By the time I started experiencing noticeable and debilitating dissociation, I’d learned not to rely on my own understanding. Adults in my life had thoroughly convinced me that I had never been abused, never experienced anything traumatic, that my childhood was entirely ordinary. As far as I knew, my mind started deteriorating with no obvious cause.

The first time I considered that I had something more than PTSD was a couple years ago. But after suffering additional trauma in 2021 and 2022, seeing a not-so-great therapist in 2023, and falling into the worst episode of suicidal ideation I’ve ever had in my life in early 2024, I was so afraid. I just wanted all of it to go away.

I resisted for a really long time, too deep in denial to stop the cycle of pain and punishment I grew up in. My abusers made me feel like a monster, and for much of my life, I treated myself like one. But at some point, all of my seemingly unexplainable experiences stopped looking like red lights and started looking like road signs. Something to point me in the direction of the truth. Over time, those voices in my head grew more and more persistent, and eventually, their presence became a signal: both shelter and warning at once.

I've been writing and rewriting this for over a year. More recently, there’s been a lot of internal debate regarding the decision to share it publicly. Talking about DID online is bound to earn you the ire of random keyboard psychologists and Reddit’s finest fakeclaimers at some point, and given the effort it already takes to live with multiple physical and psychiatric disabilities, I wasn’t super keen on inviting those folks into my comment section.

I’m still a bit concerned about that, but beyond the fear of being misunderstood, I feel equal parts protective and grateful: protective of systems everywhere and grateful for ours. I feel called to take the risk of rejection and judgment if it means someone else can feel seen in a world that works hard to erase them because, ultimately, that’s what I’m here for. I’m not one for fate, or destiny, or finding meaning where there is none, but if I can make my own purpose out of all this pain, I’d like to think I could be a lighthouse for other survivors. Living proof that life after abuse doesn’t have to be so lonely.

So, if you’re a survivor looking for the light in an otherwise dark and scary landscape, consider this our formal introduction:

My name is Eli. I’m a 23-year-old abuse survivor, and I have Dissociative Identity Disorder.

Those of you who’ve been here before already know that I’m a little strange, what with how often I write about it. That hasn’t changed. The only difference is that I’m actually just one thread in a much larger tapestry: a system of people who’ve been sharing this body, brain, and life with me since we were very small.

My headmates (the others in our DID system) have been with me through everything. They have protected me. Bled for me. Experienced horrible things and lived with the memories, all while I didn’t know about and later denied their existence. These are people who have crawled through hell with me and deserve peace just as much as I do. Who deserve to be appreciated instead of hidden away. Who I will no longer keep from you like they’re some shameful secret — because there is nothing shameful about how our brain developed to keep us alive.

What we went through is no fault of our own but of the adults who knew better and hurt us anyway. Our existence as a system isn’t something to be ashamed of.

It’s the thing that saved us.

For all the grief and pain that comes with DID — that is, with being traumatized — there is so much joy to be found in system acceptance. There is something so beautiful about living in a world that demonizes your existence and choosing to cherish it anyway. To love my system is to honor the sacrifices our brain made for our survival. To refuse shame is to honor the innocent, unprotected child we once were and all other children out there who have not known safety or love. Learning to live a happy, full life despite all the horror we’ve been through is an act of resistance and a reclamation of the power abusers stole from us when we were small.

And if that makes us monstrous, then maybe a monster is not such a terrible thing to be, after all.

For more information regarding the most up-to-date DID research, visit did-research.org. We recommend checking out the links under the DID Basics page and the Myths About Dissociative Identity Disorder.

earworms

October is a sad month for us, and that means lots of sad music. Apologies in advance for any sads that occur while listening.

I Can and I Will, to be seen, Walk Me Home, and Hold You by Searows

Fourth of July and Drawn to the Blood by Sufjan Stevens

Easy Way Out and I’ll Keep Coming by Low Roar

Father I Needed, The Window, The Mastermind, and You Are Not Him by Mac Quayle (from the Mr. Robot soundtrack)

Ptolemaea, Family Tree, and Sun Bleached Flies by Ethel Cain

Beyond Desolation and Unbroken by Gustavo Santaolalla (from The Last of Us: Part 2 soundtrack)

recent reads

It’s been a minute, so some of these were posted like…a while ago. But they still deserve all the love, so they’re included, damnit.

You are so incredibly strong and brave and I hope you wake up and know that every single day. I'm so glad you're here I'm so glad you're still fighting and you're such an inspiration in so many ways. I hope you know you're already a lighthouse <3

Eli, thank you for this. I've loved someone living with DID before and I've seen firsthand how difficult it can be to manage but also how beautiful it is to know the lengths we'll go to in order to protect ourselves and fight to keep living. You write about it all with a wisdom far beyond your years, but most importantly with heart. You've shared something beautiful and vulnerable, I hope you're proud of it.